Team 2020 has considered a variety of academic and residential life options for Academic Year 2020-21. The specific options continue to evolve as we assess them and learn more. While lack of certainty can be frustrating, it is, in fact, good: we are listening to the community, learning, and ultimately enabling more informed judgments to be made by MIT’s Senior Management Team.

Critical Background Information

For all options, we anticipate that…

- For fall 2020 at least, and perhaps the spring of 2021, most of the curriculum that can be online, will be online.

- On-campus instructional spaces will be operated in a physically-distanced way. Such constraints will limit access to learning spaces on campus, even if large numbers of students are in residence. There will be ongoing mandatory physical distancing and other now-common practices such as wearing face coverings in classroom, research lab, residential, and work spaces.

This will lead to significant changes in the ways we teach, learn, work, and live on campus.

Weighing Uncertainty

Perhaps the most important factor for judging the relative appeal and success of different options is something we cannot know with any certainty. That is…what will the future hold?

- When will easy, rapid testing be available?

- When will effective therapeutics be widely available to mitigate the most serious health consequences?

- Will there be a second wave of infections in the fall?

- Will there be a second wave of infections in the winter and significant comorbidity with the seasonal flu?

- Will there be an effective vaccine widely available by spring?

- Will we need to limit the population on campus for the full academic year?

Given these uncertainties, it is necessary to consider the various options for fall in the context of a full year. It is also critical to think about how the various options may enable us to pivot to more or fewer students, staff, and faculty on campus depending on whether conditions get better or worse.

These pivoting considerations must include changes semester-to-semester, but also within a semester, as government guidance and local public health status warrant (e.g., if we were to have to send students home early, or to potentially decide to invite more back mid-semester).

Two dominant models and example variants

As noted elsewhere on this site, there are two dominant models for operating our curriculum which have implications for the academic experience for all students: a two-semester model and a three-semester model. Each of these can be operated with varying degrees of in-person and remote education, and the timing of each can be adjusted (start and end dates).

The two-semester model is well understood, it has a variety of advantages and disadvantages for different members of the community depending on how it is implemented. The three-semester model, at the highest level, distributes the teaching over more time. So it provides an opportunity to satisfy more student needs if we have constrained instructional and residential capacity. However, it is a new model for MIT and therefore carries additional challenges. Like the two-semester model, it has a variety of advantages and disadvantages for different members of our community depending on how it is implemented.

One recent comparison of these two dominant models appears here with accompanying discussion here. The text from the chat from that presentation is also helpful to read here.

Example two-semester variants

Option 1: Invite 100% of undergraduate students to return to campus, access and operate instructional spaces in a physically-distanced way, with much of the curriculum being offered remotely.

This option is feasible if the abilities to test for, trace, and treat the disease improve rapidly in the next three months. It is less feasible if there is a late-summer or early-fall second wave of infections in the greater Boston area. It is also critical to note that MIT does not have sufficient housing capacity for a 100% return if we operate our undergraduate residences and FSILGs in a reduced density way (e.g. one student per dorm room).

In order to implement this option while upholding current physical distancing guidelines, we would need additional residential capacity (e.g., hotels) or graduate residence spaces to house undergraduates and to provide the appropriate isolation space. This would also imply greater needs for testing and tracing and may make physical distancing harder to achieve, thereby increasing the possibility of COVID infections. It is also more difficult to scale down if needed. It will strain the residential education model, with a potential need to enforce rules in a more heavy-handed way. Providing meals and dining services will be a challenge.

Option 2: Delayed start to subjects for all students (with students invited back as early as October 2020 or as late as early January 2021), then hold two regular semesters (no IAP) and potentially stretch the academic year into early summer 2021.

This option is helpful if there is a second wave of infections in the greater Boston area in late summer/early fall, and if the abilities to test for, trace, and treat the disease improve significantly sometime in the fall. We can also learn from our peers who bring students back earlier in the fall. It is less attractive if there is a second (or perhaps third) wave of infections in the winter, with the seasonal flu causing many more people to need to be tested and introducing potential comorbidity effects. Further, if we are able to operate our campus with perhaps 50% of the undergraduates in residence in the fall, and the pandemic lasts for the entire year, we would not be taking full advantage of the campus resource during the fall if we significantly delay the start.

Option 3: Invite half the undergraduates on-campus for the first six weeks, and then the other half for the last six weeks (following a two-week gap).

The fraction of the curriculum that relies on the physical instruction spaces on campus would be adjusted within each subject to take advantage of the time on-campus.

This option is attractive if health conditions improve substantially for the spring as it enables all undergraduates to be on campus for at least a part of the fall semester. However, it comes with several implementation challenges at the individual subject level and with regard to optimizing the scheduling of classes commensurate with when groups of students are invited to campus. Pivot options for the spring include repeating this split model if conditions remain the same, or inviting all students back if conditions improve (or potentially going fully remote if conditions deteriorate).

This option would give all undergraduate students some time on campus during the fall for in-person teaching and learning, in particular in lab/project/design/performance classes redesigned for this scenario. We would be able to house students in undergraduate campus and FSILG facilities in a reduced density way (e.g., one student per dorm room). Some student activities and events might be possible. With fewer students on campus, more students may be able to participate in available options while meeting constraints on density. Two weeks to enable move-out and move-in the residences is not easy, but it is feasible. There are many options for which student cohorts to bring to campus when (by class-year, by major, by social group, etc.) that all have different advantages and disadvantages. These require further study and input from the community (one focus of the charrettes).

Option 4: Invite half of the undergraduates to campus.

There are many pivot options for spring, for example inviting the other half of the undergraduate population to campus to enable equal access for all students over the year. This option is attractive if health conditions are similar in the fall and the spring so that we are constrained to operate with about half of the students on campus throughout the academic year. Students would have one semester on campus and one studying remotely. It requires less replanning of content within subjects than Option 3 but may require replanning of when classes are taught (fall or spring) between semesters to be commensurate with when cohorts of students are on campus to participate in subjects that rely on access to the physical instructional spaces. There are many options for which student cohorts to bring to campus when (by class-year, by major, by social group, etc.) all that have different advantages and disadvantages. These require further study and input from the community (one focus of the charrettes).

As with the other options with 50% or fewer undergraduates on campus in the fall, we would be able to achieve this by operating on-campus residences and FSILGs in a physically-distanced way consistent with current guidelines. When the students are on campus, some activities and events would be possible. With fewer students on campus, more students may be able to participate in available options while meeting constraints on density.

Option 5: Undergraduate students are 100% remote.

Pivot options in the spring include anything from 0% to 100% undergraduate students on campus. This option is attractive if health conditions in the late-summer and throughout the fall are similar to those we have just experienced in March, April and May 2020, with government orders in place for stringent physical distancing and business closures. It is the easiest to implement from a scheduling perspective as we would teach our current schedule of fall classes but remotely. There is also a simplicity to doing everything remotely. However, our students would not benefit from some of the educational experiences offered by in-person teaching and learning, and the residential life experience would be weakened.

An example three-semester case

Option 6: Invite 25% to 50% of undergraduate students on campus in the fall, as part of a three-semester year. Distribute typical fall and spring subjects taught over three semesters (fall, winter, and spring terms of equal length) and provide all undergraduate students with an on-campus experience for two of the three semesters.

This option is attractive for providing flexibility for a number of potential future scenarios. It enables us to begin to provide on-campus experiences to some students starting in the fall, while allowing us to increase or reduce the population in subsequent semesters. There would be no IAP and for some students, faculty, and staff, the year would extend into summer (approximately July). The availability of a “third” semester when some students are remote could be used for internships, down-time, or for making additional progress on degree completion remotely. However, implementing this option requires a more significant replanning of the academic calendar, which may have other implications on workload and staffing at non-typical times of the year. There are many options for which cohorts of students to bring to campus when (by class-year, by major, by social group, etc.), all of which have different advantages and disadvantages. These require further study and input from the community (one focus of the charrettes).

As noted elsewhere on this site, a fundamental attraction of three-semester options is they distribute the teaching over a longer period of time, thereby potentially allowing a greater satisfaction of academic and residential life needs given capacity constraints on campus instructional spaces and residences. One can also consider a variety of variants of this model with different numbers of students on campus depending on the health conditions.

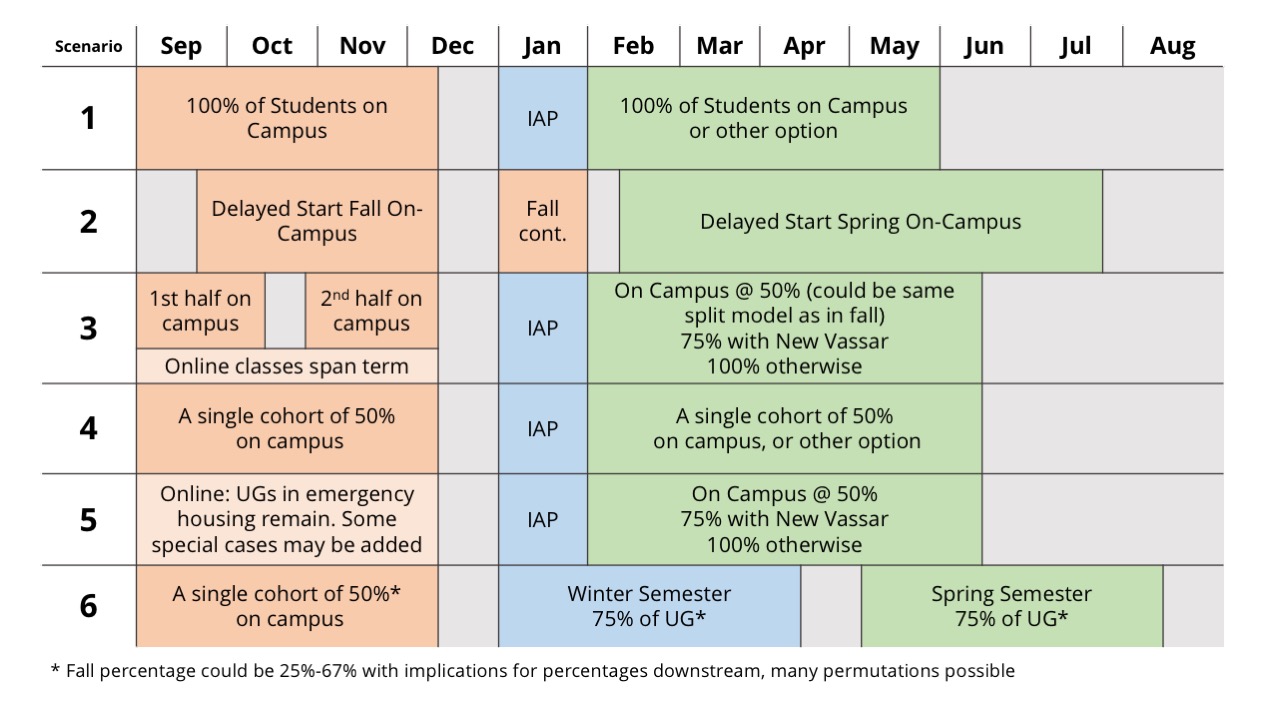

The following graphic shows how these example options may align with the calendar (note that the timing is only approximate, since the start and end times of the semesters can be adjusted for several of the options).

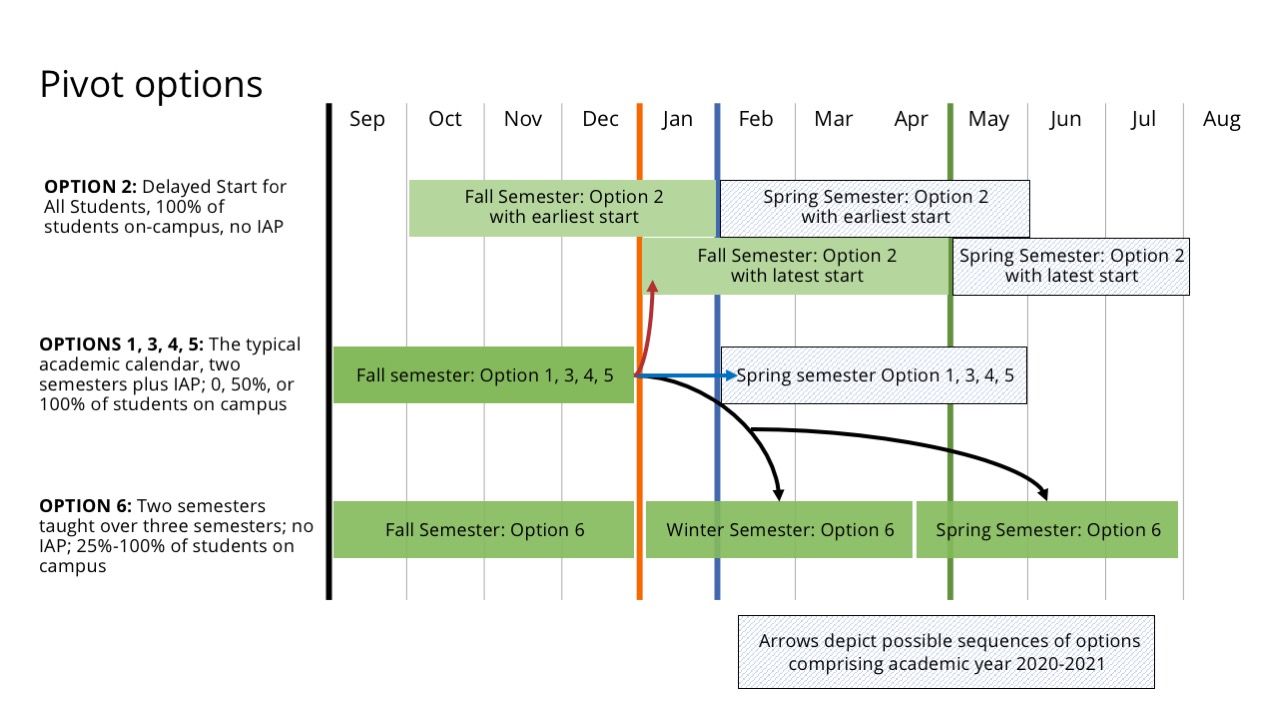

As described above, the different fall options have implications for pivoting to other options for spring. A more detailed analysis of what is possible in that regard is shown below.

—

—

Key Considerations

After reading the summaries of the options currently being considered for the upcoming academic year, it’s important to take a closer look at the common certainties and uncertainties inherent to each of them and to consider some of the steps MIT could take to make the implementation of each option more effective.

What We Know Now

During these uncertain times, some things are already clear and should be factored into the design and implementation of any option for the future. Below, we list some of them:

- MIT must meet all federal, state, and city requirements and adhere to public health orders. We will benchmark our planning and practices against the current guidance from other credible and relevant sources.

- The implementation of testing, tracing, and treatment protocols is essential to mitigating the risk of community spread of COVID-19.

- There will be ongoing physical distancing in classroom, research lab, residential, and work spaces.

- Roughly 100 fall subjects rely on access to the physical campus space to achieve the subject learning objectives. Roughly 3,000 students enroll in these subjects in a typical year. Physical distancing constraints in our instructional spaces will limit the in-person teaching that can be done on campus, and require that we teach and learn in different ways (e.g., fewer students at a time in teaching labs, design studios, project, and performance spaces and potential for broader use of the day for class hours).

- Much of the curriculum (lectures, recitations, seminars) will be offered remotely in the fall and perhaps the spring as well, even when some or many students may reside on campus.

- In the undergraduate residence halls, use of common spaces will be limited, food service options will include take-out services, and cook-for-yourself programming will likely be suspended during this period. P-setting and interactions with peers, house team members, and GRAs will be highly constrained under physical distancing. Recreational programming will be online or offered in de-densified settings. Access to common amenities such as gyms, lounges, and study rooms will be limited.

- On-campus office spaces in which staff interact with faculty, students, and other staff (e.g., DSL headquarters, DAPER check-in, OVC headquarters, SFS, S^3, OGE, MIT Medical, etc.) will need to be revamped to facilitate physical distancing. Examples include removing some furniture and chairs, putting up Plexiglass barriers and tape in lobby areas, and removing vending machines and reusable kitchen items.

- Ongoing restricted access to MIT buildings will be necessary.

- The campus will be allocated into sectors that will be entered by MIT ID-card based access. This will be less convenient and will require more planning to one’s day when coming to campus buildings to use on-campus resources. MIT is testing and adapting such approaches now with the existing on-campus population of residents, approved researchers, and campus support staff.

- Not everyone will be able to or will choose to return to campus, even if permitted to do so.

- Some people fall into a high health risk category for COVID-19 or live with people who are high risk. Every member of the MIT community must do their part to protect these members of our community. Others may be impeded from being on campus due to travel restrictions and visa delays. Still other community members may have unique living situations where teaching, learning, and/or working are made more difficult by technology barriers, family responsibilities, and financial challenges. We must be agile and able to make arrangements for individuals who are remote.

- The limited availability of MIT-owned residential beds in a de-densified campus setting poses a significant constraint. The Division of Student Life estimates the availability of 1,900 beds at one student per room and a 3:1 student/water closet ratio. Securing hotel beds may increase our capacity figures but doing so adds significant costs and presents potential negative implications for the student experience.

- We will maintain our commitment to high-quality education, student support, and co-curricular and experiential learning opportunities in every option. We will revise academic policies and regulations to respond to the plan that is ultimately put in place.

- Consistent with MIT’s mission, we will deliver “an education that combines rigorous academic study and the excitement of discovery”. We will ensure that students progress towards their degrees, minimize subject cancellations, and minimize pre-requisite disruptions. We have developed optimization methods to rapidly re-plan class schedules to achieve our objectives.

- We will maintain our commitment to excellence in research and graduate education. The research ramp up process is designed to ensure this objective.

- Creating a dedicated isolation space for students and other campus residents who test positive for COVID-19 is necessary in any of the scenarios being considered, as is a plan to scale back the reopening if community health and safety concerns necessitate a reduction in campus density levels again.

What We Don’t Know Yet

There are certain things we cannot know or guarantee at this moment, and there are certain questions we haven’t answered yet. Any option for the fall and beyond will have several uncertainties in common, including:

- The trajectory of the pandemic and the timeline for the development of a cost-effective, widely available vaccine and/or therapeutics.

- We don’t know what the public health situation will be within the city or state in the fall, including when or if a second wave will occur, when a vaccine or therapeutics will be available or once available, if we will be able to procure large enough quantities to immunize the entire community. Nevertheless, we must be prepared for dramatically changing health conditions in the next academic year (positive or negative).

- Based on what we know now, antibody testing is not likely to be helpful in the short to medium term for planning for return to campus but may be helpful eventually.

- Community members’ willingness to comply with physical distancing rules in classroom, research lab, residential, and work spaces.

- We don’t know how well students and the rest of the MIT community will follow physical distancing policies; some current residents would like stricter rules, and others would like more relaxed rules.

- Who will be allowed to travel to campus, and the best decisions for which undergraduate students will return and when for options where only a fraction of the undergraduates are on campus at a given time.

- For any case where only a fraction of the undergraduates are invited back to campus over a given period, we will have to make difficult choices about who to bring to campus and when, but we will seek to equally support and serve all of our students. We will also optimize our subject schedules to increase the ability of students to take the classes they need to progress academically.

- Space availability to enable physical distancing on campus (in our academic spaces and undergraduate residence halls).

- At current physical distancing guidelines, and taking into account the varied types of learning spaces and learning activities in MIT classes, we estimate that the academic campus can accommodate approximately 4,000 learners at a time. We could think of this as 4,000 students in classrooms/labs/studios/seminar rooms per day; or 8,000 if each student had a half-day on campus. Scheduling and judicious use of the hands-on-campus resource for in-person educational opportunities (e.g. lab, project and performance classes, design studios) for those who can be on campus will be important.

- Even as lectures, recitations, seminars, and large group gatherings are delivered remotely, individuals who choose to be on campus may benefit from physically-distanced, in-person interactions among others wearing face coverings, in medium-sized and large spaces (e.g., psetting, office hours, working on projects, practicing performances, etc.). Such spaces and the management of appropriate population density are under consideration now.

- We don’t yet know how we will house and room residential students in a de-densified scenario and may need to explore the implications of securing hotel spaces and keeping some buildings (e.g., Burton Conner and Eastgate) in use to house graduate students, undergraduate students, and/or as isolation space. Nor do we know when the Site 4 and New Vassar residence halls will open following construction delays, but anticipate this will not be until January at the earliest (these buildings provide ~450 beds each of additional capacity).

- Short and long-term impacts on the wellbeing of community members.

- While we will make every effort to create a positive and special living community on campus, some individuals may feel more isolated and have difficulties coping with the new normal. Others may have difficult living situations off-campus if they are remote.

- Short and long-term impacts on the residential education model and experience and co-curricular learning.

- There are uncertain impacts on internships, and travel-related learning.

- We don’t know the extent of necessary changes to the academic calendar and curriculum.

- Community responses and reactions to the options.

- We don’t know how many undergraduate and graduate students may wish to defer, take a leave of absence, or stay remote under the conditions in which MIT has to operate this fall. In a recent survey, when asked about the housing options they were exploring for fall, about a quarter of continuing undergraduates checked “I would probably stay where I am now if MIT has online instruction and reduced campus operations (e.g., restricted access to campus; emergency housing policies).”

Steps MIT Can Take

Keeping in mind the guiding principles and logistical, temporal, and financial realities, the following are examples of steps that MIT could decide to take that might impact the viability of the potential options.

- Consider requiring regular, community-wide testing, tracing, and treating

- Consider requiring testing on arrival/re-entry to campus and periodically thereafter. MIT Medical would be able to collect specimens for up to 5,000 viral tests per week.

- Consider requiring use of a contact tracing app to facilitate testing, tracing, and treating if we could ensure that it was accurate and could protect privacy.

- Continue to provide quarantine spaces and care for students and other campus residents who have a positive COVID-19 test.

- Continue to integrate the evolving information and protocols published in the literature into our processes for any testing, tracing, and treating as feasible and appropriate.

- Adopt new policies, procedures, and educational campaigns that promote recommended practices and support compliance with public health guidelines:

- Enhance access to hand washing stations, hand sanitizer, face coverings and work activity-specific PPE; required access control for spaces, etc. consistent with our policies.

- Enhance cleaning and stocking by staff who maintain facilities (e.g., more frequent cleaning and sanitizing schedule, restocking sanitizing wipe and hand sanitizer stations, etc.).

- Establish and communicate work-at-home policies and expectations.

- Establish and communicate expectations and protocols for being on campus (e.g., conduct meetings electronically, even when on campus; requirement to wear a face covering in any shared space; practice physical distancing; criteria to be eligible to return to campus; reminders through signage; training on new expectations; using health monitoring technology; etc.).

- Redesign spaces to help maintain physical distance (e.g., remove furniture and chairs; Plexiglass barriers; removing vending machines and reusable kitchen items).

- Establish remote, hybrid, and physically-distanced teaching, learning, and working options.

- Teach, learn, and work in new modalities.

- The entire MIT community responded quickly and effectively on short notice to the pandemic in spring 2020. Going forward, we will have more time to carefully plan and prepare. We will continue to invest in existing and new academic and well-being support structures for our students; this includes, for example, our student success coaches and other virtual support resources.

- We will redesign not only our formal curriculum but also co-curricular and experiential learning opportunities (e.g., UROP) so that we will continue to offer these exceptional parts of the MIT experience. For classes and experiences that typically require and rely on access to the physical campus space to achieve the subject learning objectives, we can explore and offer alternatives (e.g., mailing kits of parts home).

- Implement a phased or staggered campus repopulation plan.

- We can strictly limit visitors to campus.

- We plan to ramp up the research enterprise under the following parameters:

- Reduced occupancy and density levels for our buildings and labs as prescribed by our medical and public health professionals. PI and DLC operating plans will align and be benchmarked against these levels.

- Only researchers and staff needing to use the physical campus will be allowed back during the ramp-up process. Clearly, this need is subjective and thus a period of comment and discussion with the faculty is underway to plan phases of research ramp up that would increase the number of MIT ID holders coming to campus to conduct research each day. Researchers and staff who can work remotely will continue to do so until conditions as determined by our medical and health professionals allow them to return to campus.

- Individual PIs and DLCs will be empowered to structure their research activities in response to these new occupancy and density levels. Priority should be given to activities that can easily be scaled up or scaled down if necessary.

- Core facilities, shared resources, and other services will be made available to facilitate research activities broadly, provided they can function safely and within the predetermined limits regarding occupancy and density.

- Access to buildings (and, where possible, individual spaces within buildings) will adhere to approved PI personnel plans; only those individuals who are approved to enter buildings will be allowed to do so and will do so through specific building access locations and protocols.

- Anyone who chooses to participate in on-campus research can be supplied with face coverings or PPE if needed. Face coverings or masks will be required to be worn while working in MIT buildings. On-campus personnel will follow physical distancing protocols as described in PI space planning documents and DLC plans for common spaces. They can also submit to a daily health attestation as well as possible health monitoring and testing.

- Researchers, students, and staff returning to campus to conduct or support research may be expected to enroll in an online environmental, health, and safety training course to learn about how to maintain a safe and clean work environment in the current COVID-19 era conditions.

- Create and promote new modes of operating for student life and hands-on learning opportunities as well as community-building programs.

- New virtual study lounges and other study spaces (remote and physically-distanced in person) could be used to promote academic belonging, peer-learning, and camaraderie.

- New campus organizations and events (e.g., discussion groups, representative bodies, etc.) can help anticipate and manage the range of issues that will arise in a physically distanced academic year.

- Adapt MIT’s business operations to all options.

- Essential campus services must be staffed according to acceptable campus density parameters and guidelines for safe working conditions and safe commuting. The research ramp-up plans, educational plans, and other MIT programs cannot create an unacceptable burden on these functions or these campus service staff.